On a recent night in the South Bronx, Fernando Laspina peeked out the front window of El Maestro and Juan Laporte’s Boxing Gym and saw a cold, steady rain falling on the dimly lighted, rugged streets of his troubled youth.

“When I was teenager back in the early 1970s, I used to run around like crazy all along Southern Boulevard out here,” said Mr. Laspina, shaking his head. “I was a leader of a street gang called the Savage Skulls. I was young and very foolish at that time, and I paid for it by going to jail.”

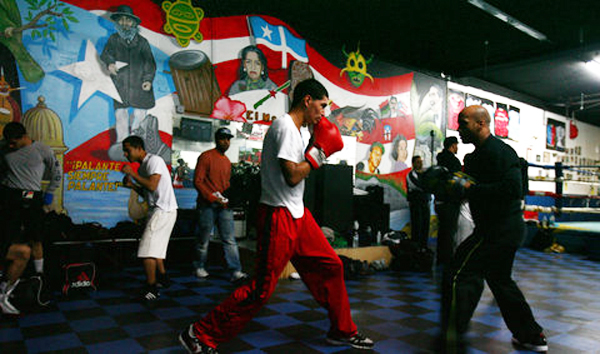

Mr. Laspina, now 57, took a step back from the window and captured a much brighter scene in its dusty reflection: dozens of young men scattered in and around a tattered boxing ring, sparring, jabbing at speed bags and jumping rope.

“This is my dream come true,” said Mr. Laspina, turning toward the stable of young boxers with a proud smile. “By keeping busy in here, they are not out there getting into the kind of trouble I got myself into when I was a kid. To have a place like this has been a goal of mine since I got out of prison, a promise I am still keeping to my mother.”

Mr. Laspina, who juggles his role as the executive director of El Maestro with his day job as an afterschool coordinator for the New York City Housing Authority, is now hailed as a hero on the same streets he once terrorized.

“I’ve known Fernando since the mid-1970s,” said Ramon Jimenez, a lawyer and political activist who lives in the neighborhood. “In the 40-plus years I’ve spent in the South Bronx, I’ve met many politicians and many famous people, but I’ve never met anyone with the dedication, commitment and endless energy and refusal to be defeated like Fernando ‘Ponce’ Laspina — his story stands above the rest.”

Mr. Laspina, one of 18 children born in Ponce, P.R. — “that’s where I got my nickname,” he said — was 15 years old when he and his family settled into the area, which was already crawling with street gangs.

“I couldn’t speak English and I had some trouble fitting in,” he said. “Before you knew it, I was getting jumped and guys were robbing what little money I had. I actually joined a gang to help protect myself.”

His mother urged him to leave the Savage Skulls, and Mr. Laspina, who by then was pretty good with his fists, tried obliging her in October 1973, when he signed up to join a boxing organization run by the Police Athletic League. Later that same week, he was arrested for extortion and sent to Rikers Island.

Under the headline “5 in Bronx Youth Gangs Indicted in Merchant ‘Protection’ Racket,” an article in The New York Times published on Oct. 19, 1973, began, “Scores of shopkeepers in the South Bronx have been terrorized by street gangs into paying ‘protection’ money to escape beatings, arson and robbery.” The article named all five who were indicted, including, Mr. Laspina, who was 18.

“My mother was crushed, and it really hurt me to let her down like that,” he said. “That’s when I promised her I would never let her down again and that when my legal troubles were behind me, I was going to turn my life around.”

After spending nearly a year on Rikers Island, Mr. Laspina was freed on bail while awaiting trial. After a conviction and much legal wrangling, he served another year at the Elmira Correctional Facility in Elmira, N.Y., starting in 1975. While in prison, he earned a general equivalency diploma.

Shortly after his release, Mr. Laspina joined Mr. Jimenez and a band of students and faculty members in a successful challenge to plans to shut Hostos Community College or merge it into another institution during the city’s fiscal crisis.

“It was the only bilingual college in the area and it was on the brink of closing down,” Mr. Laspina said.

He soon enrolled at Hostos, where he received an associate degree. He went on to Lehman College, where he received a bachelor of arts degree, and then to Buffalo State University, where he earned a master’s in Latin American studies.

In 2003, Mr. Laspina founded his dream organization, which is run by volunteers.

“My mom lived long enough to see it,” said Mr. Laspina, whose mother died in 2007. “She lived long enough to see me turn my life around and fulfill that promise.”

El Maestro has been at its current location, 1300 Southern Boulevard, next to an abandoned lot, for two years, having moved, Mr. Laspina said, because he could no longer afford the almost $4,500 a month in rent for the old site. He now pays $3,000 a month, some of which comes out of his own pocket.

The organization’s two main missions — it serves as both a cultural center and a training center — are spelled out on each side of the long, red awning above the front door. The south side of the awning, which reads “El Maestro Inc.,” is a center of Puerto Rican culture and heritage named for Pedro Albizu Campos, the deceased Puerto Rican nationalist leader who was known as El Maestro (The Teacher).

The north side of the awning, which reads “Juan Laporte’s Boxing Gym,” is named for the former featherweight champion who was born in Guayama, P.R., and is a friend of Mr. Laspina’s.

Julio Pabon, a South Bronx activist and a local businessman who ran with a street gang named the Young Lords in the 1970s, called Mr. Laspina “a good example of what the Bronx has to offer.”

“Most of my friends and Ponce’s friends are either dead or in jail,” Mr. Pabon said. “Ponce didn’t just survive; he is now helping other people survive.

“In the South Bronx, our schools are not the best and our role models are few and distant. We have a very high unemployment rate, one of the highest obesity rates in the country, violent crime and inadequate housing, so the deck is stacked against any young person here who is trying to make something of their life.

“Without Ponce, I can’t imagine where these kids would be today.”

Mr. Pabon was talking about children like Jeffrey Cuadras, an 11-year-old from the neighborhood who is learning how to box.

“I like coming here because I feel safe,” said Jeffrey, lacing up a pair of gloves as he peeked out the front window of the gym. “There’s nothing out there but robbers and drug dealers, and I don’t want to end up like that.” By Vincent M. Mallozzi [NYT]