“What’d you learn in the lab today, Daddy?”

“How the brain works.”

“Why do you want to learn how the brain works?”

“To help people with spinal cord injuries.”

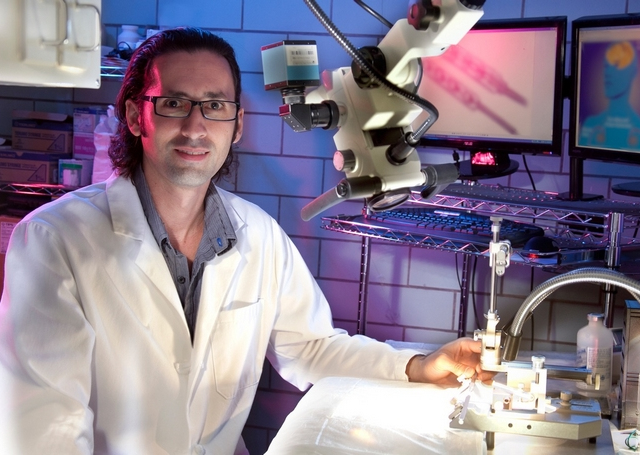

Over ten years of toiling in the lab on chronic implanted microelectrode arrays for human neuroprosthetic applications boiled down to a phrase a toddler can understand. But Dr. Sanchez sees his answer to his daughter as the true motivation behind his work.

Restoring motor control to paralyzed patients doesn’t just mean designing the electrodes, explains Dr. Sanchez. “I’m trying to fix a major problem in somebody’s life. It’s not science just for the sake of doing science. It’s trying to do something that’s really meaningful to somebody.”

There is no way to reverse damage done to the spinal cord. Spinal cord injuries impact nerve signals from the brains causing patients to lose control over their arms and legs. Patients with these injuries have modern devices available– smart wheelchairs, voice-controlled computers, electrical stimulators that control muscles–but none that can inconspicuously restore function to limbs. Dr. Sanchez and his research team at the Miami Center to Cure Paralysis are on the verge of discovering new technology that could reroute brain signals around the spinal cord injury, giving patients the ability to move their own limbs without “wheeling around huge computers or robots,” Sanchez says.

And that, he says, is what patients want.

“People don’t understand how complicated somebody’s life becomes when they have a spinal cord injury. Every time you wanted to go to the bathroom you’d have to have someone help you do that. For me, that’s devastating,” he says.

Sanchez, a Tampa native, grew up with a love of science. “I always knew I wanted to solve problems,” he says. Once he began attending private school, his tuition put a strain on the family’s finances. His mother taught English at the local elementary school and he says he would often have to help out at his father’s steakhouse. “My family sacrificed a lot for me. Educationwas very important to them.”

Sanchez went on to earn an engineering degree from the University of Florida, then a master’s and PhD in biomechanics. Along the way, he taught himself advanced computer programming. The technology he’s working on blends all of those disciplines. “People that work in this area have to be cross-trained,” he says.

His team of neuroscientists, engineers, and computer programmers spend seventeen-hour-days in the lab on the federally-funded experiments that could lead them to human clinical trials. They monitor electrodes in animals and perfect neural decoding algorithms. Sanchez says he hopes to reach human application by early 2013 but, he’s already been struck by how quickly the field has evolved.

“When I first started my career in this area, it started off as a kind of a dream, something that was really frontier. But now it’s getting to a point where we can make viable medical therapies. It’s been an interesting journey along the way -and it’s been fun!” by Nadine Natour [NBC]